Carlos Rafael made an offer the bank couldn’t refuse.

It was February 2021, and Rafael, the infamous New Bedford fishing mogul known as “the Codfather,” was serving out the final stretch of an almost four-year prison sentence. He and his two daughters placed a USD 770,000 (EUR 708,000) bid to acquire the Merchants National Bank building in downtown New Bedford, Massachusetts, U.S.A.

The historic sandstone building with tall arched windows and an ornate ceiling no longer functions as a commercial bank. It’s vacant, and there is no money locked behind its heavy iron vaults. But, for the 71-year-old Rafael – flush with more than USD 70 million (EUR 64 million) in cash from the court-mandated sale of his fleet and barred from involving himself in the commercial fishing industry ever again – acquiring the bank set the stage for a second act.

Three years after his release from prison, Rafael, still banned from owning fishing vessels, has embarked on a different business venture: a multimillion-dollar real estate financing operation sprawling across New Bedford and its suburbs.

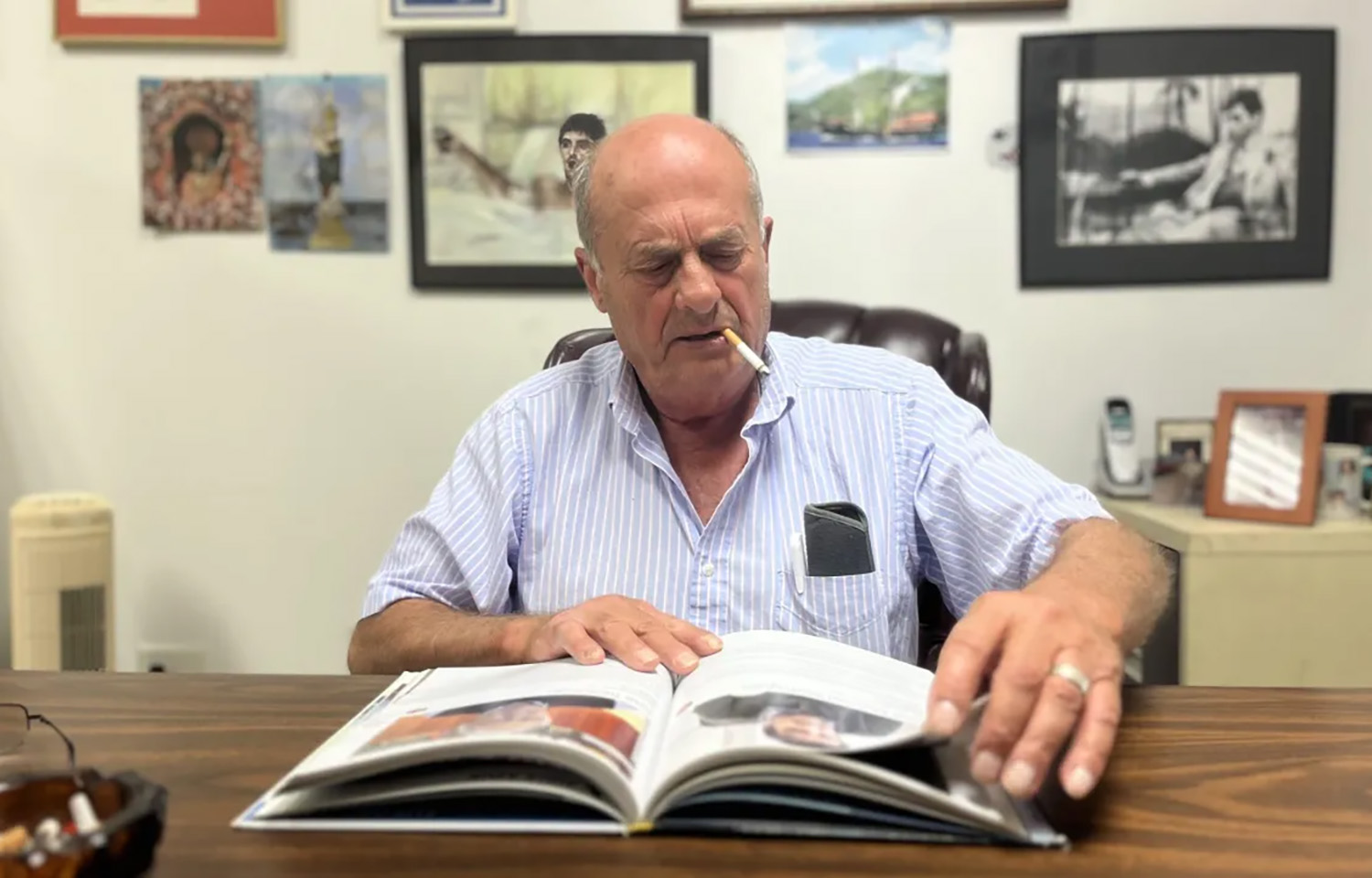

“I’m the bank now,” Rafael said in a recent interview, leaning back in his dark leather office chair in his South End industrial warehouse. The wall behind him was adorned with paintings of Catholic saints, multiple sketches of Tony Montana – Al Pacino’s gangster protagonist in Scarface – and a sea-green miniature replica of one of the three-dozen fishing vessels once part of his fabled fleet.

“You have no clue how relieved I am to be out of the fishing industry,” he continued in his low, raspy voice, pausing only to sweep flakes of cigarette ash off his desk. “This here: finance. It’s better than the fishing business. You shitting me?”

Since his release from prison in 2021, Rafael has parlayed the spoils of his fishing empire into a series of high-profile real estate deals and lower-key private loans. He’s lending to developers who are aiming to renovate and flip properties throughout the South Coast of Massachusetts.

Property records show Rafael has financed 25 of these renovation projects, adding up to a total of just over USD 7 million (EUR 6.4 million) over the last three years. They range from vacant, boarded three-deckers in the South End to one-story ranch houses in Dartmouth and freshly developed mansions on a cul-de-sac in rural Westport.

Rafael’s own real-estate purchases include a defunct, 15,000-square-foot nursing home in New Bedford, which he bought at auction in 2022 for USD 770,000, and a subdivision on a USD 200,000 (EUR 184,000) vacant lot in Dartmouth, Massachusetts. Most notably, he acquired the abandoned Hawthorne Country Club in Dartmouth, wresting it from former owner Kevin Santos by buying out the mortgage for USD 2.3 million (EUR 2.1 million) in 2021. The neglected clubhouse was set on fire last year before Rafael could flip the property to luxury real estate developers, and one man has since been charged with arson.

Meanwhile, earlier in 2024, the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center bought the former headquarters of Carlos Seafood from Rafael for USD 2.3 million to expand its offshore wind facilities. Rafael’s estate also continues to collect interest on a USD 23 million (EUR 21 million) principal owed by Quinn Fisheries, which acquired his scallop vessels in 2020.

Rafael’s financial services aren’t cheap, he said. The private loans he has dished out to a handful of developers are short-term, requiring repayment after only six months. The average loan is USD 291,000 (EUR 267,000). The interest rate: 14 percent.

“I’ve seen a lot of gangster stories. Some, they call this loan sharking,” he said. “But, I know how to make money the right way, too. Sure, you have to pay taxes up the yin-yang, but screw it. [These are] legit real estate deals. No other asshole in the city of New Bedford is making 14 percent on his money. Not in fishing. No way.”

Today, Rafael runs his operations from the back office of a warehouse. The warehouse is surrounded on all sides by stacks of rusted fishing gear – trawling winches, scallop dredges, tangled mountains of net, and yellowing ice boxes filled with shackles and scrap metal – marking the skeletal remains of his once-mighty fishing fleet.

An immigrant from the Portuguese island of Corvo, Rafael arrived in New Bedford in 1968 as a teenager and then ascended rapidly from a fish cutter to the owner of the largest groundfish company on the East Coast. It’s an empire he built by way of ruthless capitalism. As fishing regulations tightened and hard times fell on the industry, he seized on the opportunity to expand, buying the businesses of friends and rivals alike as they teetered on the brink of bankruptcy.

By 2016, Rafael was ready to cash out of the seafood business. He had cornered as much as one-fifth of New England’s groundfish quota, along with boats and permits for scallops, lobster, squid, and mackerel.

But, in an attempt to sell his fleet, Rafael was caught in an Internal Revenue Service (IRS) sting operation. He flipped his books open for two undercover federal agents posing as Russian mobsters and divulged the long-running scheme he called “the dance.” It involved intentionally mislabeling fish to evade regulatory quotas. Rafael’s illegal overfishing added to the rapid depletion of already struggling groundfish stocks. He was sentenced to 46 months in prison for 27 counts of tax evasion, cash smuggling, and fraud related to mislabeling over 800,000 pounds of fish.

As part of his plea deal, Rafael was forced to sell his fleet. He closed the deals while behind bars at the Fort Devens federal prison in Massachusetts. He sold the scallop vessels to New Bedford-based Quinn Fisheries and the groundfish vessels to private-equity-backed Blue Harvest Fisheries.

Quinn Fisheries has continued to expand since it bought Rafael’s scallopers. Rafael allowed the company to defer payment for 10 years, he said, instead paying only interest on the USD 23 million debt. But, Blue Harvest Fisheries since filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in fall 2023. The private equity firm bankrolling Blue Harvest claimed a loss of USD 209 million (EUR 192 million), while countless small businesses in New Bedford were left with millions more in outstanding debts.

In a November bankruptcy auction, the Canastra family bought eight groundfish boats that had once belonged to Rafael’s fleet. A month earlier, the last of Rafael’s groundfish vessels that still bore his fleet’s distinctive green markings – older vessels that were no longer seaworthy – were carved into scrap metal and transported to a recycling center in Middleborough, Massachusetts.

Rafael netted a total of USD 102 million (EUR 94 million) on the sale of his fleet, he said. After taxes and a fine of USD 3 million (EUR 2.8 million) imposed by fisheries regulators, he was left with just over USD 70 million waiting for him upon his release from prison. His only other penalty: a lifetime ban from the commercial fishing industry.

“I was forced out at the right time,” Rafael said. “Today, I’d be in big trouble. My boats would be worth maybe half of what I got for them.”

Many New England fishermen, specifically those who played by the rules and suffered during Rafael’s reign, said the fines were inadequate. Rafael profited handsomely for his crimes, they said, while many small-scale, independent fishermen were left to sink while abiding by the strict regulatory system that Rafael worked so hard to evade. Fisheries regulators, however, said they achieved their goal.

“Our goal was to remove Carlos and his family from the fishing industry permanently. That was the priority,” said John Bullard, a former New Bedford mayor who served as regional administrator of NOAA at the time of Rafael’s downfall. “That meant, by selling his fleet and assets, he was going to end up with a lot of money.”

Now, Rafael is putting some of that money back into circulation in New Bedford.

“He can do anything he wants as long as he stays far away from the fishing industry,” Bullard said. “I urge anyone who wants to do business with him to realize that tigers can’t change their stripes. Watch out who you are dealing with.”

In New Bedford, real estate prices and rental rates have skyrocketed, spurred by speculative investors and increased demand. Low-income renters, squeezed out of rapidly gentrifying Massachusetts cities like Boston and Worcester, are settling in New Bedford, where rents are comparatively cheap.

The economic conundrum is a headache for both developers and city housing officials. Though construction prices are about the same as in other cities, rents are much lower, making profit margins razor-thin and financing difficult to secure. As a result, despite record demand, over 570 housing units remain vacant in the city as of September 2023 – most due to abandonment or neglect of dilapidated properties.

Those seeking profit in flipping houses say private lending is the only viable option.

John Afonso, a 44-year-old developer from Dartmouth, is one such person pursuing private lending. In 2023, Rafael loaned Afonso USD 300,000 (EUR 276,000) to renovate an abandoned three-family apartment building in New Bedford’s Weld Square neighborhood. The building was plagued by inattention that caused a thicket of weeds to engulf its chain-link fence; a stream of yellow caution tape blocked off its front steps.

“A traditional bank is not going to give me a loan to fix a house that has fire damage, needs a roof, the heat doesn’t work, and the water is shut off,” Alfonso said. “A private investor will.”

Today, the once-abandoned tenement shows signs of new life: fresh siding, new windows, and a child’s bicycle leaning against the porch. The caution tape is gone and replaced with decorative streamers festively celebrating U.S. Independence Day.

Sitting in his office in the South End, Rafael balks at the suggestion of altruism playing a part in his investments.

“All I’m doing it for is to make money. I have a shitload of money, and this makes me more,” he said. “If it benefits New Bedford, good, but it’s not because I want to. I could give a good fuck about what happens to the city of New Bedford. It’s because I want to make a profit.”

In late June 2024, Rafael was preparing to board a flight to his home island of Corvo. He recently renovated his childhood home there and shipped out his 28-foot pleasurecraft, on which he says he plans to spend time fishing for deep-sea bass, marlin, and tuna. It’s an annual vacation, he said, but this year, he plans to declare residency in the Azores, he said, which requires him to live there for six months and one day each year.

The reason, he said, is to evade the U.S. estate tax, which after one’s death allows the government to collect up to 40 percent of the value of an estate with assets over USD 13 million (EUR 12 million). Through his lifelong bout with the IRS, which has twice landed Rafael in prison, he said he refuses to lose the final round.

“I am going to fight these motherfuckers until the day I fucking croak,” he said, stubbing out a cigarette he said he bought off an Indian reservation to avoid paying the state’s high tobacco tax. “The government didn’t win. I win. They fucking lose.”

This article originally appeared in the New Bedford Light on 10 July.