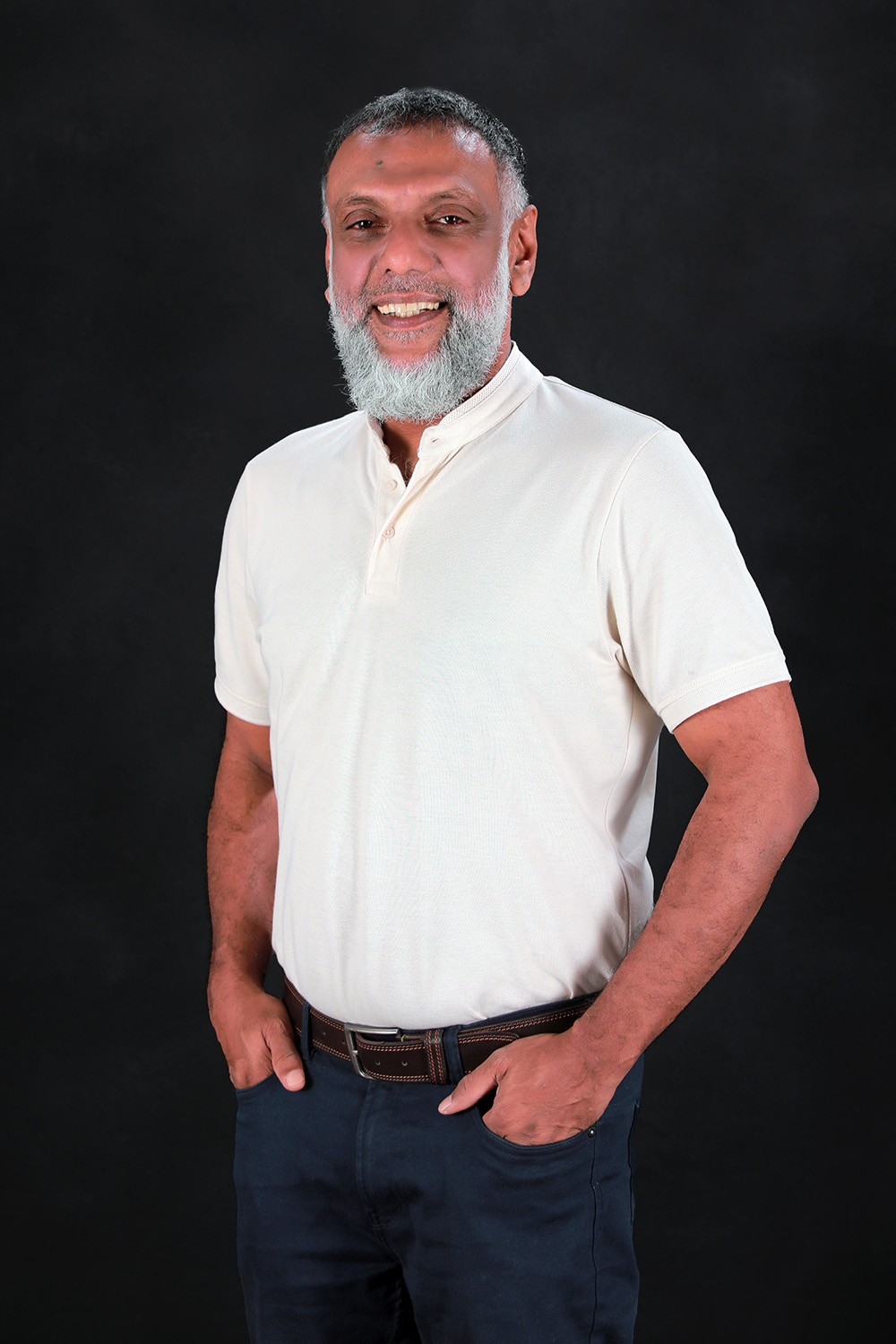

In his mid-40s, Irfan Thassim had a comfortable position as the CEO of a subsidiary of one of the largest and most admired companies in Sri Lanka. Thassim had been with his company – a major player in the country’s textile and apparel industry – for 20 years. While he worked hard, overall, life for Thassim was relatively easy.

That made Thassim uncomfortable.

“I was thinking, I've got a 15- to 20-year professional horizon left. Do I want to continue in the same fashion?” he said. “The answer was no.”

After many long talks with his wife, Thassim began looking around for something else to do.

“I looked at our resources in Sri Lanka, which is a tiny island of 65,000 square kilometers with 20 million people living on it. The largest resource that we have is the oceans. When I started looking into that, I realized there was a lot more that we can do with them,” he said. “But, it was completely new to me. I grew up in a little coastal town on the southern coast of Sri Lanka. We would literally play cricket and volleyball on the beach. I had a love for the oceans because I grew up on them, but doing business there was not something that I had [considered].”

As a first step, Thassim flew to England, where his sister was living. He had hopes of flying on to Norway, which he knew was an aquaculture hub, but he couldn’t afford the plane ticket. So, instead, he ended up in Scotland.

“I heard about Stirling University’s expertise in aquaculture, so I called them up and I said, ‘Look, I've got this idea to start a project in Sri Lanka, but I don't know zilch about aquaculture. If I were to come by, can you do a rundown for me of what I need to know?’ They told me to come on over, so I did. I spent half a day running through the entire history and the potential future for the aquaculture industry. Looking back, I call it my half-day MBA in aquaculture,” Thassim said.

The following day, Thassim began making cold calls to Scottish aquaculture companies, trying to arrange a meet-up with anyone willing.

“Only one person returned my call, and that was [Kames Fish Farm Managing Director] Stuart Cannon. I ended up at his [farm] site the next morning, and he took me out on a boat; I got to see the first fish cage I had ever seen, and it was love at first sight,” Thassim said. “After that, I couldn't get it out of my head why an island like Sri Lanka, having such a vast oceanic resource around, had not ventured into this industry. My decision was made then and there that Sri Lanka's going to get this.”

That was 2012. Five years later, Thassim had founded South Asia’s first barramundi farm and received his first lease for a site in Trincomalee, on Sri Lanka’s east coast.

Thassim chose to name his new company Oceanpick to render an image of a bountiful harvest and completed a four-cage pilot project that lasted through 2016. Then, Oceanpick ramped up to 20 cages and, in 2017, added a second site. At the same time, it worked with Sri Lanka’s government to create aquaculture regulations, which previously didn’t exist.

“There were no regulations because there was no history of marine aquaculture. Government officials would literally ask us how they should monitor us,” Thassim said. “I kind of realized early on that it was our responsibility to do it right – as a pioneer of this industry. We were setting the precedent for an entire industry, and we needed to be the benchmark."

Oceanpick leaned heavily on the Scottish Environmental Protection Authority standards to help shape its own standards, as well as Sri Lanka’s as a whole. That involved lots of communication between Sri Lankan and Scottish officials and members of the industry.

“When I look back, I don’t know how we did it. Honestly, it's puzzling to me years later,” Thassim said. “For somebody who didn't know the industry as well, it was a lot of painstaking effort, learning, and staying patient with both our systems and the regulatory system.”

Thassim received help from Stuart Cannon and Kames Fish Farm, which had entered a joint venture with Oceanpick that involved the sale of equipment and the lending of a heavy dose of expertise.

“We really relied on Kames and all of the 50 years of experience they had because they were absolute pioneers of trout farming in Scotland,” Thassim said. “I didn't let them just to sell me stuff and walk away. I convinced them to become a joint venture partner. I twisted their arm, and I said, ‘No, you have to take a stake in the business. You have to stay on my board, and you've got to kind of drive us through this.'”

Still, it wasn’t easy.

“Between 70 and 80 percent of my time was spent trying to avoid bankruptcy, trying to keep the lights on. Companies like ours need waiting time – and plentiful resources. You need resilience to continue. There are no shortcuts in this business. We had a lot of trial and error and things we experimented with and had to change,” he said. “All that is a key part of entrepreneurship. If the fundamentals are right, you can succeed.”

Right as Oceanpick was finding its stride, Sri Lanka’s seafood industry was dealt a blow with the delivery of a European Union red card, which banned seafood trade shipments from Sri Lanka to the E.U. The ban was rescinded in 2016, but the incident gave Thassim a greater purpose in his work.

“It was only then I understood that Sri Lanka was grappling with IUU or being recognized as a country that was not compliant in many ways with global fisheries standards. Out of that, my own motivation kind of grew to showcase Sri Lanka as ... offering a sustainable source of fish,” he said. “There is a lot of a lot of pride that I take in that this was a Sri Lankan initiative.”

Nevertheless, Oceanpick struggled for many years after it was founded. Fry imported from Australia was not growing well in its cages. By 2018, Thassim said he was ...