Regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) play an important, though sometimes opaque, role in fisheries management and governance. In the last few years, with the help of pre-competitive collaborations like the Global Tuna Alliance (GTA), supply chain companies have become more engaged in RFMO management issues to the benefit of the entire industry.

The first in a four-part series covering the role regional fisheries management organizations in the global seafood trade. The series is intended to help seafood companies better understand the role and impact of RFMOs and the opportunities to engage with those bodies.

RFMOs are international organizations and arrangements formed by countries with fishing interests in a geographical area or a highly migratory species, such as tuna. These organizations have the authority to establish fisheries conservation and management measures on the high seas outside of the exclusive economic zones (EEZ) of individual nations.

“An RFMO is formed by both countries in the region (“coastal states”) and countries that have interests in those fisheries but aren’t necessarily geographically there (“distant-water fishing nations’). They’re [RFMO members] the ones who decide what happens, so they decide quota allocations, effort controls, closures at sea, and they set all of the other requirements,” GTA Executive Director Tom Pickerell said.

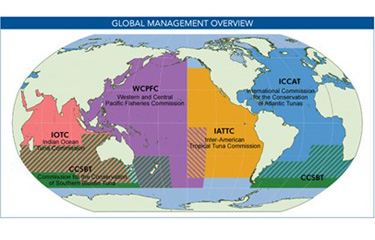

There are 17 RFMOs in total, of which five are focused on tuna management and together cover about 91 percent of the world’s oceans. A majority of commercial marine fish stocks are managed by one or more RFMOs.

“In terms of tuna management, tuna is a high-seas fishery, so it appears in the high seas in international waters as well as exclusive economic zones. Because of that, we need to have management that goes beyond national waters. To address that, there are the five tuna RFMOs," Pickerell said.

RFMOs have a significant impact on the seafood industry, as they create fishing limits of certain species including bluefin tuna and yellowfin tuna, and perform stock evaluations. RFMOs also create rules regarding transshipment, labor, and retaining of bycatch species. These rules have overall impacts on catch limits and import/export legalities that impact the entire seafood supply chain.

RFMOs are often categorized into three different types: geographical/general RFMOs, tuna RFMOs, and specialized RFMOs. General RFMOs have a wide scope to adopt measures for most fisheries in their specified geographical areas and tend to focus on fishing methods, such as bottom fishing, pelagic, and bentho-pelagic fishing, instead of fish species. Tuna RFMOs aim to protect tuna stocks in specific areas such as the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. Specialized RFMOs focus on specific types of fisheries or species and tend to have less of a geographic coverage due to their specification.

Though the RFMOs are generally categorized in these three types, each RFMO has the ability to manage specific species or fisheries based on the need of that area. For example, many RFMOs based in a geographical category will still have quotas on a specific commonly caught endangered species or non-migratory stock, rather than just fishing methods.

Establishment of the RFMOs occurred at a time when ocean resources were believed to be unlimited. Therefore, it was not a high priority to create a structure that could limit fishing. RFMOs can play an important role in protecting fish stocks and the overall long-term sustainability of the global seafood supply, but continued challenges like illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing and transshipment, as well as the challenge of implementing science-based solutions via the RFMOs’ consensus-based decision-making process, all reduce the effectiveness of RFMOs, according to Pickerell.

“RFMO participants are, to varying degrees, flexible and open to influence through lobbying. This is evident by the substantive engagement of the catching sector in RFMOs, both on flag-state delegations and as observers. In comparison, the influence of retailers and other supply-chain members has been far less significant and often apparently completely absent,” Pickerell said. “We are relying on the RFMOs to effectively manage the fisheries they are responsible for. However, they have to improve. Some of the recent decision-making is not aligned to sustainable management and is driven by short-term thinking by many of the delegates.”

The reliance of retailers and other supply chain companies on RFMOs can sometimes cause issues. Hamish Walker, the chief operating officer of Denver, Colorado, U.S.A.-based Seattle Fish Company and a member of the pre-collaborative nonprofit Sea Pact, said Sea Pact became involved with RFMOs as issues arose within the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), an RFMO covering tuna in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. The main concern was the possibility of WCPFC fisheries losing Marine Stewardship Council certification, potentially damaging the sales and business relationships of seafood suppliers dealing in tuna from the region.

“We, as a mid-supply chain company – as all Sea Pact members are – are not dealing directly with the producers abroad, so we don’t have a lot of control of the upstream supply chain, but what we desperately need is product that meets our own sustainability requirements and that we can sell to our U.S. customers that our U.S. customers can trust. If the Western Central Pacific loses its MSC status, that takes out a whole chunk of supply that we then don’t have access to; so, it suddenly becomes really quite economically important to us,” he told SeafoodSource. “That was why we got involved with the RFMO for the Western Central Pacific.”

Fisheries management by RFMOs isn't without its obstacles, however. IUU fishing presents a significant challenge, because scientific committees depend on transparency and accountability on catch totals in forming fishing mandates and limits. When unknown amounts of fish are taken by illegal activities, limits can be set at unsustainable levels, causing harm to legitimate businesses. A 2020 report by researchers at the University of British Columbia and University of Western Australia found illegal fishing costs between USD 26 billion to USD 50 billion (EUR 24.7 billion to EUR 47.5 billion) in annual economic impact due to this diversion of fish from legitimate trade.

Transshipments – another problem confronting the world’s RFMOs – occur when fish are loaded from one ship to another to complete a journey, often outside EEZs. These shipments are not subject to clear rules through RFMOs, and are sometimes linked to illegal activity, including illegal fishing. The Pew Charitable Trusts estimates at least USD 142 million (EUR 134.9 million) of tuna and tuna-like species are moved via illegal transshipments each year in the western and central Pacific Ocean alone.

Tackling those issues, Walker said, is essential for the seafood industry.

“If we are going to have a future in seafood business, we need product for the long-term and we need product that our customers can trust. It’s hard for our smaller customers to know all the specifics of the fisheries they buy from and they do look to us as a trusted source and to have confidence we’re doing the right thing. We need to honor that trust and back it up,” Walker said.

The last major challenge for RFMOs is their decision-making process. RFMOs are structured around a principal decision-making body – the commission – composed of a number of delegations made of each participant country. There are members that actively participate in voting and are subjected to regulation, as well as cooperating non-members that do not vote or have financial obligations but are subject to the same regulation as members. Lastly, RFMOs have subsidiary bodies to provide advice and specific functions, such as a compliance committee, which ensures compliance with RFMO decisions, and a scientific committee, which provides advice to the commission on decisions regarding fishing management options.

The voting system for rule changes in RFMOs can be consensus-based or based on a simple majority vote. The consensus-based system, which requires the agreement of every RFMO member for a motion to pass, can make passing new rules or changes to existing rules difficult.

The scientific committee gathers the data to develop stock numbers for the annual commission meeting and then propose those standards to the commission, everyone must agree for it to pass. There is a tendency for one or two countries to hold the process back which hampers any progress for a year or two. In that time, not only can stocks plummet, but also any enforcement to reduce IUU or illegal activities is paused allowing these illegal organizations to develop advanced methods to hide illegal operations.

“I don’t know if this is all of them, but certainly for the tuna RFMOs, you can object to a regulation and if you do then you don’t have to follow it – instead the previous measure, if there is one, applies,” Pickerell said. “We have this in the Indian Ocean, where the yellowfin [tuna] is overfished. The [Indian Ocean Tuna Commission] created a rebuilding plan last year in the Indian Ocean. It was the absolute minimum and even then, six countries objected and said the regulations didn’t apply to them. If the [objecting countries] catch what they caught previously, the rebuilding plan will be shot to pieces and it’ll be the second-highest catch of yellowfin ever. It just demonstrates the futility of it all.”

RFMOs cover a majority of the high seas and could be an important tool to monitor fish stocks for long-term ocean health and food security. But many organizations believe RFMOs have failed to prevent depletion of high-seas fish stocks and degradation of marine ecosystems. Changes must be made for confidence to return and for active and effective management of globally important fish stocks, Pickerell said. The creation of pre-competitive collaborations like the GTA is one way companies are trying to make those changes.

“GTA have added a market voice to it [RFMO decisions]. If the supply chain doesn’t buy the tuna, there is no industry for anyone. We’re trying to come in with a voice to say this is what we want to say and it is very aligned with what the NGO community has to say. In order to change the dynamic, we are trying to use commercial power to influence what’s happening,” Pickerell said.

Some stakeholders are working collaboratively to develop proposals to improve the performance of RFMOs, including efforts to replace the decision-by-consensus process with a two-thirds majority system. Individual seafood businesses and nonprofits and NGOs have issued proposals to implement automatic catch-allocation schemes, such as harvest-control rules and petitions to require RFMOs to conduct regular performance assessments. Some have called for a greater use of intersessional decision-making across multiple annual meetings, rather than one high-stakes meeting annually.

On these efforts and in relation to future advocacy for reform and advancement, there seems to be broad agreement on the need for greater industry engagement with RFMOs, Sea Pact Executive Director Sam Grimley said.

“Being able to get the global industry together that are working through these pre-competitive efforts, such as Sea Pact or the Global Tuna Alliance, and align them so they’re collectively working to engage the RFMOs is critical,” Grimley said. “It’s a challenge to be a single company trying to approach a delegate that is going to an RFMO and expressing their support for a management measure. In order to efficiently drive impact, it has got to be a coordinated effort across the global industry that’s dependent on these resources to advocate for change at the RFMO level.”

Image courtesy of The Pew Charitable Trusts