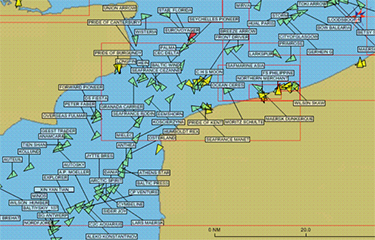

Fishing vessel location data from Automatic Information Systems (AIS) has shown promise to illuminate fishing activities around the world for fisheries managers and researchers, especially in the far reaches of the ocean and in regions where monitoring is limited.

But despite its potential to aid researchers and fishery managers, it’s not a perfect tool.

Not all vessels use AIS, which was originally developed to aid with navigation, not track illegal fishing or fishing effort. The algorithms that have been developed to interpret AIS data can have trouble distinguishing between different gear types. And the technology illuminates fishing activities in some regions of the ocean better than others.

A new global atlas reviews the ability of AIS to accurately track fishing vessel activity, and shows where low AIS adoption rates and high numbers of small and artisanal vessels complicate the picture.

The 400-page atlas was released this week during the International Symposium on Fisheries Sustainability hosted by the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome. It uses a dataset from Global Fishing Watch of the AIS signals of 60,000 vessels, of which 22,000 could be matched to publicly available vessel registries.

The atlas looks at the opportunities and challenges of analyzing fishing activity using AIS.

"Realizing this potential, though, is not straightforward and depends on the vessel size, gear type, and the species targeted," the report authors wrote.

The atlas finds that AIS data is useful for tracking large vessels – those above 24 meters – as well as those from upper and middle income countries, those on the high seas, and distant water fleets. But the vast majority of the world’s 2.8 million fishing vessels are under 24 meters, and those rarely carry AIS. Captains can also turn off AIS transponders more easily than Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) equipment – or they can broadcast inaccurate identity information.

The effectiveness of AIS also varies regionally. AIS effectively documented fishing activity in the North Atlantic, for instance, but didn’t in the Eastern Indian Ocean, which had the highest disparity between results from AIS data and data from other sources. The industrialized fleets of the Northwest Pacific and Northeast Atlantic commonly carry AIS technology, while small and artisanal fleets in the Global South often don’t. In Southeast Asia, even large vessels often don’t carry AIS, and reception is lacking.

The algorithms currently used to interpret AIS data were able to effectively classify the gear types that large vessels use, such as longlines, trawls, and pelagic purse seines, but didn’t differentiate as well among gears used by smaller coastal vessels, such as gillnets, trollers, and pots and traps.

The atlas concludes that AIS can viably estimate fishing effort in real time, but data and trends still need to be verified and supplemented with logbooks, VMS information, and other sources.

"AIS can start to be considered a valid technology for estimating fishery indicators. This atlas reveals both promising findings and key limitations of inferring fishing effort from AIS data,” the report notes.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons