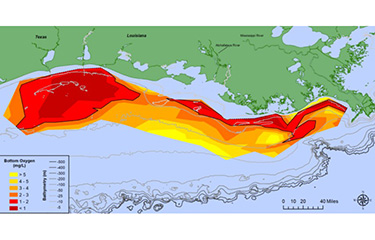

NOAA announced on Tuesday, 3 August that its scientists have determined the size of this year’s “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico to be more than 6,300 square miles, a figure that’s both above the recent average and well above what officials initially forecasted in June.

The “dead zone” is term applied to the hypoxic zone that is annually established in the Gulf of Mexico. Fed by agricultural runoff, the Mississippi River dumps nutrient-rich water into the gulf, leading to algae growth during the spring and summer months. As that dies and sinks to the bottom, bacteria decay the algae but also consume oxygen in the process, resulting in an area of the ocean that is considered unsustainable for marine life.

The dead zone this year, at 6,344 square miles, equates to more than four million acres that is toxic to fish and other species.

The size of the zone was surveyed last week by scientists from Louisiana State University and the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium. This year’s survey found surface waters with little salinity. A release from the federal agency said that was likely due to recent above-normal discharges from the Mississippi River.

NOAA Principal Investigator Nancy Rabalais said in a statement this year’s zone was different that ones in previous years.

“The area from the Mississippi River to the Atchafalaya River, which is usually larger than the area to the west of the Atchafalaya, was smaller,” said Rabalais, who is also a professor at Louisiana State University. “The area to the west of the Atchafalaya River was much larger. The low oxygen conditions were very close to shore, with many observations showing an almost complete lack of oxygen.”

This year’s zone is slightly smaller than the size of Hawaii, which covers 6,423 square miles. It’s also 17.7 percent larger than the average zone over the past five years. The zone is also roughly three times larger than the 2,035-square-mile goal the hypoxia task force set for the gulf.

Two months ago, NOAA announced a forecasted size of 4,880 square miles for the zone. That forecast was based in part on lower than usual nutrient totals found in the Mississippi in the spring. While the zone was nearly 30 percent larger than forecasted, scientists said it is still within the expected range.

Photo courtesy of NOAA/Louisiana University of Marine Consortium