A newly developed histamine sensor can quickly and inexpensively measure histamine – the cause of scomboid poisoning – without the use of reagents.

At 18th Seafood Show Osaka on 17 and 18 March, Tetsuya Kuwabara, the chief engineer of engineering development at Fujidenolo Co., Ltd., displayed the device at the booth of the Osaka Fisheries Research and Education Organization, and presented a seminar on it on the 17th. Fujidenolo is based in Komaki City, Aichi Prefecture, Japan. It manufactures and sells medical and healthcare products and also makes various plastic components.

Histamine is an organic compound involved in local immune responses. It is naturally released from “mast cells” (a type of connective tissue) in the human body when the mast cell is exposed to an antigen. Histamine is useful, as it allows white blood cells to permeate the capillaries so that they can engage with pathogens in infected tissues. However, it also triggers inflammation, itching, sneezing, and nasal congestion.

Bacteria can also produce histamine. The non-infectious foodborne disease “scomboid poisoning” is caused by histamine production by bacteria in spoiled fish. Symptoms may include flushed skin, headache, itchiness, blurred vision, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea. Onset of symptoms is typically 10 minutes to an hour after eating and can last for two days.

Histamine is usually produced when fish is not promptly refrigerated after harvesting, especially in hot weather, as in tropical tuna or mahi. Freezing or cooking inactivate the bacteria, but do not destroy the histamine that was already produced.

In his seminar, Kuwabara noted the number of cases of scomboid poisoning in Japan in the decade stretching from 2009 to 2019. In total, there were 94 incidents with 1,915 people sickened. Many of these occurred in school or company cafeterias. There were 20 outbreaks with 355 victims in 2018, and eight outbreaks with 228 people affected in 2019. The cases typically involved consumption of oily blue-skinned fish, such as Pacific saury, mackerel, and tuna. Though some cases were from consumption of sashimi, cooking does not destroy histamine.

While there are currently tests that can detect histamine, they require the use of reagents and are typically performed in a laboratory, taking about one hour, Kuwabara said.

“The concept of the new device was that it should be a system that allows quick testing for histamine anywhere, anytime, by anyone,” Kuwabara said.

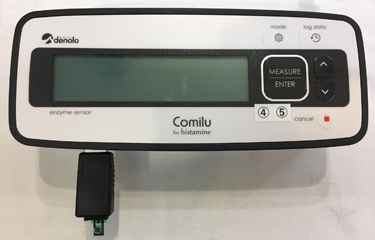

The newly developed Comilu device is compact and it takes under 10 minutes to prepare and test a sample. The system includes the electronic device, a chip adapter that plugs into a USB socket, the sensor chip, a syringe for placing liquid sample on the chip, and a screw-press. A small portion of seafood – such as could be picked up with tweezers – is placed in the syringe. The syringe has a screen at the small end to allow liquid to pass while keeping back solids. The syringe is placed into the screw-press, which can then be turned to apply pressure to the syringe plunger.

A couple of drops of liquid are squeezed out to the sensor chip and the “measure” button is pressed. A measurement of histamine in parts per million (ppm) is returned in seconds. The measurement range is 0 ppm to 500 ppm, with an error range of plus/minus 10 percent. The test data (up to 80 measurements with date and time) can be logged and later transferred to a computer.

To clean the sensor, the drop can be gently absorbed with a tissue and a drop of clean water dropped. This is repeated with salt water and again with clean water. Then an air blower is used to dry the sensor chip. It is then ready for another test.

Part of the inspiration for the battery-operated device was home-use glucose test devices for diabetics, although histamine’s chemistry make it more difficult to detect. The idea that anyone can perform the test easily makes it possible that the tests are not only performed by processors, but also in institutional foodservice centers, such as school cafeterias.

The company literature promotes such uses as checking raw materials before buying at the place of purchase, and checking processed products with colorings or flavorings that could make it hard to judge freshness by color.

While less raw fish is eaten in the United States than in Japan, histamine is still a problem. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration reported the investigation of an outbreak of scombrotoxin fish poisoning in yellowfin tuna in November 2019 and recommended that all tuna from Vietnam-based company Truong Phu Xanh Co., with production dates in 2019, should be discarded. Customers of eight U.S. importers were asked to confirm the origin of their tuna. That incident caused 50 cases of illness, with one hospitalization.

Photo courtesy of Fujidenolo Co.