Aquaculture monitoring technology has gotten caught up in a propaganda campaign across state media and social media warning about the dangers of “foreign spies” in China.

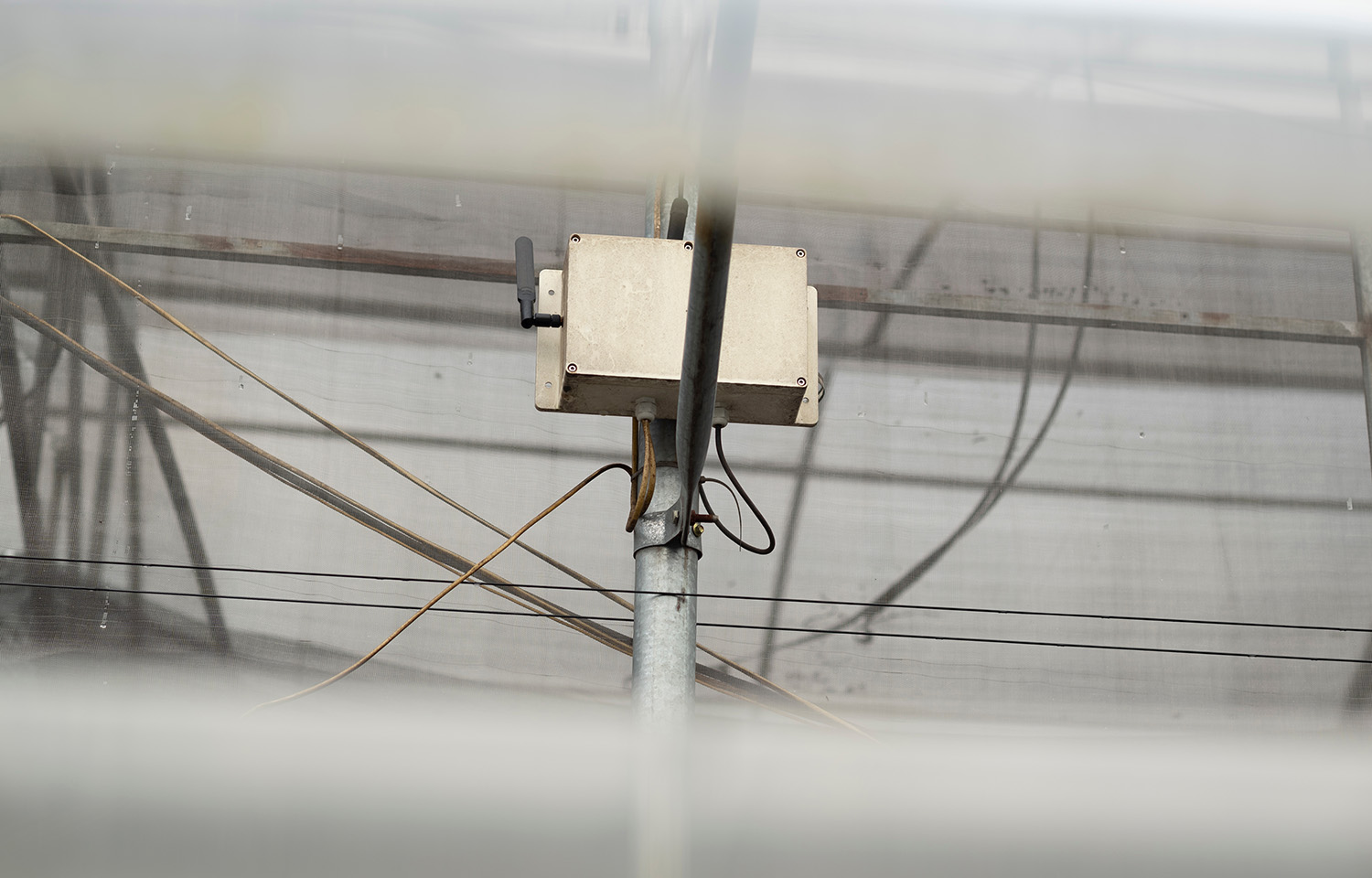

A China Central Television’s Legal Channel 9 report that ran recently on several state media channels featured a Dalian resident identified as “Mr. Zhang,” who said he was visited by several uninvited foreign equipment suppliers in 2019 and agreed to have them install water-quality monitoring equipment at his sea cucumber farm.

After becoming suspicious, Mr. Zhang decided to call a newly created hotline set up by China’s police to take calls from the public about suspected espionage. Zhang said he “gradually discovered” that data from hydrological monitoring equipment was being transmitted overseas, and that much of the data had nothing to do with sea cucumber farming. After an investigation, the authorities allegedly confirmed to Zhang the equipment installed at his farm was being used for sea and air surveillance and recording of military movements.

“[This posed] a serious threat to my country's maritime rights and interests and military security,” Zhang said.

The Chinese government’s heightened preoccupation with national security culminated in a revision of the country’s espionage law last summer. The changes to the law widened the scope of what can be regarded as a state secret and what information can be shared with overseas entities.

The impact of the change may harm innovation and development of China’s aquaculture sector, and may hinder cooperation with foreign researchers and consultancies, according to Kevin Fitzsimmons, a University of Arizona professor specializing in aquaculture.

“I’m not sure what ‘competitors’ or ‘enemies’ would do with pond dissolved oxygen, pH, fish density, and feeding rate data. But politicians will spin it somehow,” Fitzimmons said. “Nationalistic posturing hurts everyone and will hold back technical developments all-round.”

There are broader commercial implications for China’s prioritization of national security. Fitzsimmons said particularly impacted by China’s crackdown on supposed foreign espionage are the due diligence companies conducting research into Chinese companies for clients seeking to invest in or purchase a Chinese company or industry. Several have closed their offices in China in the past year after police raids at foreign-owned risk consultancies in Beijing and Shanghai.

At the same time, U.S. politicians have pursued a ban on Chinese social media platform TikTok over security concerns, and U.S. authorities have prosecuted numerous Chinese nationals for spying.

“It is unfortunate that both sides have reached this level,” Fitzimmons told SeafoodSource. “Overblown concerns about TikTok are leading to overblown concerns about spying in China. Of course, TikTok collects data and of course aquaculture monitoring systems collect data. That is how they work. The aquaculture data is pretty benign, but if it is stored in the ‘cloud’ someone else could access it.”

Fitzsimmons had tongue-in-cheek political advice for both nations.

“Put the scientists in charge – we get along with everyone,” Fitzsimmons said.

Photo courtesy of Nguyen Anh Mai/Shutterstock